Continuity between Prenatal and Labor and Delivery Care Serving a High-Risk Urban Population

Posted in SBSM What's New

- Authors: Carol Davis, PhD, MBA; Thomas DeLeire, PhD; Yetong Xu; Rehman Liaqat

- McCourt School of Public Policy, Georgetown University

Abstract:

This brief study measures continuity between prenatal and delivery care in Safe Babies Safe Moms’ (SBSM) population and explores the association of that continuity to patient demographics and health history, birth outcomes, and delivery costs in SBSM’s inaugural year. The results help contextualize our health economics research and recommendations for SBSM.

SBSM is a program of MedStar Health to improve perinatal outcomes in Washington, DC. SBSM is supported by a 5-year grant from the Clark Foundation. SBSM is building clinical program interventions, enhancing support systems, and connecting patients with vital community service partners to improve outcomes for mothers and babies at birth and well beyond.

Introduction:

Continuity between prenatal care and birthing at MedStar Washington Hospital Center (MWHC) deserves particular attention as a juncture in patient flow and data management that influences outcomes we can observe and evaluate for clinical and cost effectiveness.

SBSM augmented services at OB/GYN Specialty Care and several more clinics in DC serving populations where rates of adverse perinatal outcomes were most severe. During 2021, the SBSM program augmented multidisciplinary services at prenatal clinics, and began implementing new screening and care bundles focused on priority health conditions potentially impacting pregnancies – hypertension, diabetes, anemia, and behavioral/mental health. MWHC is the delivery hub of SBSM’s care delivery sites. In 2021, ~25% of DC moms, and over ~40% of moms residing in Wards 7 & 8 (Southeast) delivered at MWHC.

Historically, walk-in deliveries have been associated with excess costs and barriers to efficient labor and delivery care (Miller 2005, Shaw 2008). Electronic health records have greatly improved records access, but barriers still exist when patients transfer clinics or walk-in to hospital for delivery. SBSM has made efforts to improve communication and records access with local clinics that frequently provide prenatal care to patients served by MWHC, but more remains to be done on this front.

Methods:

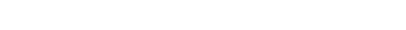

We used a retrospective cohort design to track the prenatal and delivery encounters of ~3,500 persons delivering their babies at MWHC in 2021. We split patients into 3 groups, based on prenatal relationship with MedStar and SBSM. Patients with at least 3 prenatal visits at MedStar were included in this study subgroups 1 or 2.

- Group 1: OBGyn Specialty Care Prenatal Patients

3 or more visits to the clinic with the highest concentration SBSM service enhancements in the program’s first year.

- Group 2: Others with MedStar Prenatal Visits

This group includes patients seen at any MedStar OB Clinic, including patients who were occasional patients at OB Gyn Specialty Care.

- Group 3: Walk-In Deliveries

This group includes patients who delivered at MedStar Washington Hospital Center, but were not prenatal patients within the MedStar records’ system.

Data for this study was generated from MedStar internal sources. Prenatal history of Group 3 patients is beyond this study. Analyses and data formatting were conducte

Results:

Two-thirds of patients who delivered babies at MWHC got prenatal care from MedStar Health. A slight majority of these prenatal patients had 3 or more prenatal visits at MedStar’s OB Gyn Specialty Care Clinic.

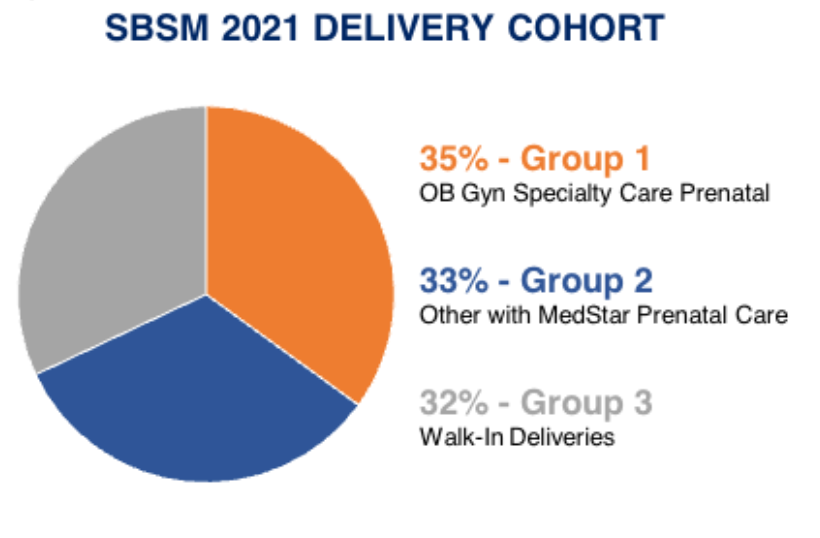

Demographic differences between Prenatal Groups and Walk-Ins were statistically significant, but not of a magnitude that can be considered operationally distinct. Patients in subgroups of particular interest: Black, Residents of DC Ward 7&8, Medicaid recipients were a greater proportion of the prenatal patients(Groups 1 and 2) and of the Walk-Ins (Group 3).

Beginning in 2021, SBSM began implementing new screening and care bundles for 4 health conditions potentially impacting pregnancies –hypertension, diabetes, anemia, and behavioral/mental health. Records from 22% of Group 3 patients showed diagnostic markers of these preexisting health conditions. By comparison, 44% of Group 1 patients had one of the 4 conditions documented. In Group 2, 38% had markers of these preexisting health conditions. Both results were significant at the p<.001.

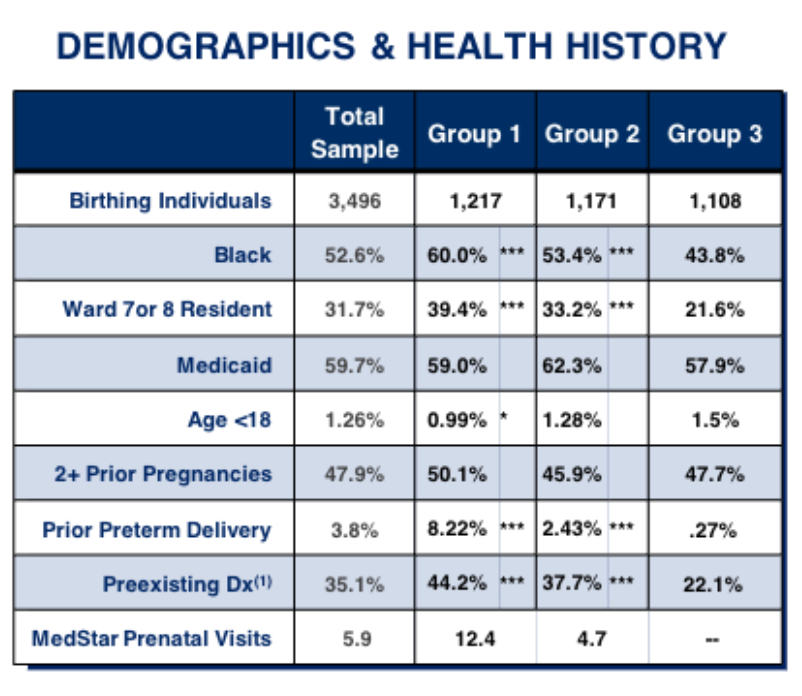

(1) Patients diagnosed during prenatal or delivery admission with any of the following: Hypertension, Diabetes, Anemia/Blood Disorders, Depression/Mental Health Conditions prioritized in SBSM interventions implemented during 2021

Despite lower rates of preexisting conditions of interest, Group 3 patients had a higher rate of preterm and extremely premature births. That result was significant at the p<.01 level compared to of MedStar prenatal patients in Groups 1 and 2. Occurrence of babies with low birthweight were mixed, Group 3 had fewer than Group 1, but more often than Group 2. These results are unlikely to be attributable to sampling alone. More than half the moms in all three groups experienced some complication during labor and delivery. Prenatal patients’ records had higher occurrences of these diagnoses than Walk-Ins. These differences were significant at the p<.05 level. Average cost per delivery for Walk-In patients was between the cost of the prenatal patients, but with the large standard deviation relative to the mean costs, the differences were not statistically significant.

*p <.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001 compared to Reference Group 3

(2)Source for Frequency of Birth Outcomes- Preterm Birth and Low Birthweight is NPIC Reports. Source for Extreme Prematurity is based on newborns with final MSDRG #792, as the primary diagnosis.

(3)“Complications” captured for this analysis include ICD-10 codes for Complications in L&D, excluding preterm or long labor.

Source: Georgetown HCFI Analysis of data from MedStar Health for SBSM Health Economics Research.

Limitations and Next Steps:

We interpret the results of this preliminary analysis with great caution, due to three primary limitations: i) The evolving nature of the SBSM clinical implementation, ii) yet-to-be settled consensus on operating definitions for elevated risk and iii) reliance on billing systems designed for discrete payment transactions to assemble a comprehensive, longitudinal view of each patient served by MedStar. These findings are highly sensitive to patient groupings, how analysis of the delivery process is operationalized, and with a purview limited to MedStar data.

Despite the limitations, our findings offer several insights for refining the analytical framework, and for expanding capabilities for management information that support this work in real time. Going forward, the health economics team will continue to partner with SBSM work groups to further distinguish the patients and services most impacted and benefitting from enhanced services through SBSM and at MWHC.

Conclusion & Insights for Practice:

Our preliminary findings illuminate differences between the experience of the group of patients receiving prenatal care at MedStar Health before their delivery at MWHC and those who walk-in to deliver.

Using data from the early period of SBSM’e enhanced clinical interventions, this analysis suggestes Despite a higher prevalence of markers of risk of adverse outcomes, the rate of actual adverse outcomes (as captured in final Dx) was lower- reinforcing the value of prenatal care and continuity with the birthing unit. Even in its inaugural year, a higher “dosage” of SBSM (Group 1) was correlated with a lower rate of some adverse outcomes compared to the patient group that walked-in (Group 3).

We recognize that this preliminary analysis is not yet refined enough to tease out the drivers of these results or to confidently assert the magnitude of the differences. Several possible contributors: continuity of care, SBSM, prenatal care in general, factors sorting patients into the various utilization groups, communication and records access at the birthing admission, This brief exploration will guide refinements in our analysis and ultimately our conclusions about the impact of SBSM outreach, interventions, and delivery process on perinatal outcomes for vulnerable moms and babies in Washington, DC and beyond.

References:

Miller, D. W., Yeast, J. D., & Evans, R. L. (2005). Missing Prenatal Records at a Birth Center: A Communication Problem Quantified. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings, 2005, 535–539

Shaw, K. J., Gutierrez, M., Fridman, M., & Gregory, K. D. (2008). Health care costs associated with changing clinics and “walk-in” deliveries: evidence supporting a regionalized health information network. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 198(6), 707