Return on Investment from Safe Babies Safe Moms; Evidence from the 2023 Cohort

Posted in SBSM What's New

May 2025

Authors: Carol B. Davis, PhD, MBA, Assistant Research Professor & HCFI Associate Director

Aditi Bhardwaj, MS, Data Scientist, Massive Data Institute

Yuhan Ma, MS, Research Assistant

Vika Li, MS, Research Assistant

Thomas DeLeire, PhD, Interim Dean, Distinguished Professor, HCFI Director

All authors are affiliated with the Health Care Financing Initiative Research Center at the McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown University.

📄 Download the full handout (PDF)

Click here to access it. Includes the full evaluation framework, references, and institutional acknowledgments.

Introduction

Safe Babies Safe Moms1 (SBSM) is an innovative perinatal care program integrating enhanced clinical protocols for common maternal risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, iron deficiency, and maternal mental health conditions. In addition, SBSM also included screening and interventions for health-related social needs to expand and accelerate initiation of prenatal care.

These factors contribute to the high and disparate rates of adverse perinatal outcomes among the diverse, and often under-resourced, population served by MedStar Washington Hospital Center. Safe Babies has achieved impressive results for a population in the District of Columbia that has historically experienced disproportionately high rates of preterm birth and other adverse perinatal outcomes.

The costs and consequences of suboptimal birth outcomes are diffuse, spanning across sectors and time horizons, making it difficult to galvanize immediate, coordinated action and to operationalize sustainable financial support for proactive interventions that extend outside the boundaries of traditional health care. This is especially true when the prevailing environment is one of fiscal contraction and sector-by-sector cost containment. Our study takes a pragmatic approach to measuring the impact of the Safe Babies program by applying a policy-salient time horizon and adopting a “customer” perspective—emphasizing the financial implications for payers and health systems who would be asked to bear the direct cost to scale and sustain the program. This study updates and expands our ongoing evaluation of return on investment (ROI) for the SBSM enhanced prenatal intervention, incorporating the most recent data from the 2023 cohort to evaluate ROI as of discharge from hospital after delivery/birth.

1This report uses the terms moms and mothers to refer to people who experience pregnancy and birth. We acknowledge that not everyone who gives birth identifies with these terms, and we aim to use language that is both inclusive and accessible.

Data and Methods

Our study sample2 included mother-baby dyads delivered at MedStar Washington Hospital Center between January and September 2023 , and who also received prenatal care in the MedStar Health system from January through September 2023 (n=1,610) compared to dyads with deliveries from July and December 2020 (n=984). Moms were further segmented into one of the three risk classes based on their clinical conditions and pregnancy characteristics3. We further stratified our analysis by insurer, separating Medicaid from Private Insurance payments.

To assess the return on investment (ROI), we first estimated the number of preterm births avoided by comparing observed rates to expected rates, adjusting for risk factors and using a difference-in-differences approach between SBSM and Other MedStar prenatal groups.

Second, we calculated the value of each preterm birth avoided as the average difference in reimbursement at birthstay4 between preterm and full-term dyads.

Third, calculated short-term return on investment by calculating the excess of birthstay payments saved divided by the incremental prenatal patient care costs plus the indirect program costs. This estimate was performed for the entire ObGyn Specialty Care cohort, and for patients in the Priority Conditions Risk group.

To assess the robustness of our results, we conducted one-way sensitivity analyses on the improved rates of preterm birth, and on the $ value per preterm birth avoided.

2Sample Groupings: ObGyn Specialty Care prenatal patients w/ 3 or more visits at ObGyn Specialty Care Clinic represent the Safe Babies Safe Moms treatment group for this analysis. Other Medstar patients with prenatal visits, in the MedStar system, including patients with fewer than three visits to ObGyn Specialty Care serve as the comparison group.

3Clinical Stratification: Prenatal patients with hypertension, diabetes, iron deficiency anemia, anxiety or depression were classified with Priority Risk Conditions. Prenatal patients with none of the priority conditions, but with selected other conditions- prior preterm birth, prior cesarean, multiple gestation, delayed start prenatal care, infections, other blood disorders, pelvic abnormality, aged 35+, parity >3 were coded with Other Clinical Risk. Patients with none of the above conditions are designated as Normal Risk for preterm delivery.

4Primary Outcome: Birthstay refers to the joint inpatient hospital admission for the mother’s delivery and the hospital stay of their newborn infant. It captures the full continuum of care during and immediately after birth and serves as the central outcome for cost, payment, and clinical results in this study.

Results

Program Costs: The incremental cost of the additional prenatal care provided as part of SBSM ObGyn Specialty Care patients in 2023 was $1.65k for each of the 981 ObGyn Specialty Care prenatal moms. Indirect program costs added another $2.2k per mom. In aggregate, the incremental cost of SBSM was $2.77M for the ObGyn Specialty Care.

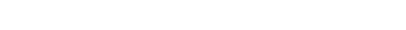

Trend in Preterm Births: We compared the rate of preterm birth from 2023 to 2020 in ObGyn Specialty Care prenatal cohorts by risk class, finding the rate of preterm births for Moms with Priority Conditions declined to 14%, (CI90:12 -17%) and a Difference-in-Difference (DiD) improvement of 14%. Compared to 2020, the rate of preterm birth in 2023 among dyads with Other Clinical Risks was statistically unchanged at 8%, (CI90: 6 -10%). Among patients with Normal Risk for preterm birth, the rate declined to 7%, (CI90: 1-12%) between 2020 and 2023 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Adjusted Rate of Preterm Births by Prenatal Group and Risk Class, 2020 – 2023

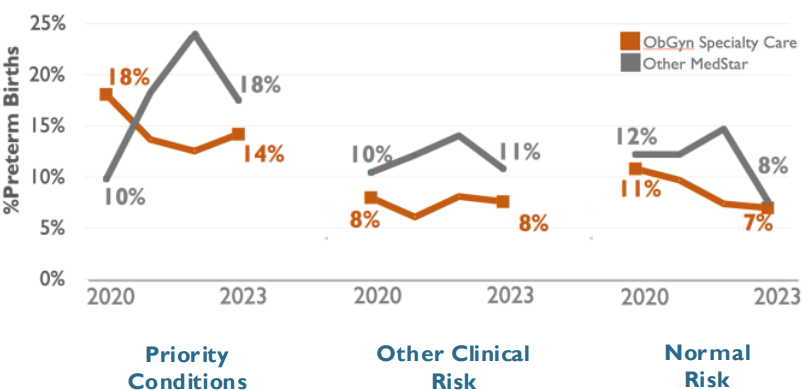

Using a Difference-in-Difference analysis by Risk Class, we estimated 59 preterm births avoided within dyads with Priority Conditions, and 62 preterm births avoided overall. The robustness of these results will be bolstered by a larger sample, but, on a year-over-year basis, evidence of the relative improvement within the SBSM cohort continues to accumulate.

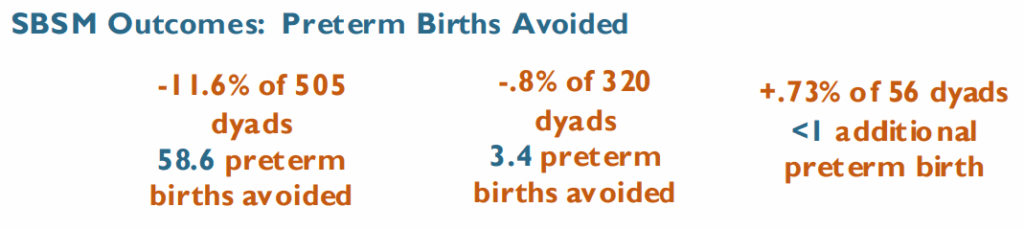

Savings in Birthstay Payments: The difference in average birthstay payments between full-term and preterm birthstays represents the financial value to payers of each of the ~62 preterm birth avoided. For Medicaid dyads, the observed difference was $37.3 (CI90: $25.1 – 49.6). The analogous difference for privately-insured dyads was $100.6 (CI90: $43.3 – 157.7) (Figure 2). In aggregate, the reduction in preterm deliveries resulted in an estimated birthstay savings of $3.76M.

Figure 2. Average Payment at Birthstay by Payer and Birth Outcome, ObGyn Specialty Care

We estimate ~62 fewer preterm births in the ObGyn Specialty Care cohort from Jan – Sept 2023, saving $37k per Medicaid dyad and $100k per privately insured dyad.

Return on Investment: As of 2023, SBSM resulted in an aggregate birthstay savings to payers of $3.76 M from incremental prenatal costs of $2.77M, for a benefit/cost ratio of 1.36 (return on investment of 36%). The ROI of SBSM if restricted to patients with Priority Conditions is 138% (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Short -Term Return on Investment in SBSM as of YTD-3Q-2023, ROI at the Birthstay

Limitations

- Our analysis offers a policy-relevant view of the incremental ROI in SBSM, reflected in birthstay payments for both mother and baby—currently assessed primarily by preterm vs. full-term status. Incorporating measurable maternal outcomes, ex: precursors to severe maternal morbidity will enable more complete reporting of program impact.

- This assessment uses the mother-baby dyad as the unit of analysis, as the financial impact of prenatal care is often reflected in the baby’s birthstay costs. Average payment for preterm newborns is over 3 times and 5 times the full-term newborns for Medicaid and Privately insured patients respectively. Separate insurance coverage for mother and baby in Medicaid complicates linking costs and savings to a common financially- accountable health plan.

- Evaluating outcomes through the postpartum period would offer a fuller view of program impact. This study was limited to data availability at MedStar clinics and MWHC, capturing only part of postpartum and pediatric care.

Implications for Policy & Practice

Our estimates of the short-term results of Safe Babies Safe Moms suggest that the enhanced prenatal, behavioral, and social care interventions can achieve a positive return on investment by the time mom and baby are discharged from the birthstay. However, these results are dependent on payer mix and revenue models.

Reducing preterm births—a core aim of the program—means reducing the frequency of high-acuity clinical events for high-needs patients, a core component of academic medical centers’ expertise. Accordingly, hospitals may face perverse incentives in the absence of adjusted payment models. This is especially true where Medicaid funds the majority of the cases, and operating margins on dyads with healthy birth outcomes are very thin. Our analysis suggests that payer-specific redesign of funding arrangements is feasible and essential to scale and sustain SBSM going forward.

Acknowledgements

Our work was completed with the cooperation of the SBSM project leadership from MedStar Health Research Institute. Financial support was provided by the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation.

Suggested Citation

Davis CB, Bhardwaj A, Ma Y, Li V, DeLeire T. Return on Investment from Safe Babies Safe Moms Evidence from the 2023 Cohort . Poster presented at MedStar Health – Georgetown University Research Symposium, May 2025, Bethesda, MD

References

- Patchen, L., et al. Safe Babies, Safe Moms: A Multifaceted, Trauma Informed Care Initiative. Matern Child Health J 28, 31–37 (2024)

- Thomas, A. D., et al (2024). D.C. Safe Babies Safe Moms: A Novel, Multigenerational Model to Reduce Maternal and Infant Health Disparities. NEJM Catalyst, 6(2), CAT.24.0161

- Hall, E. S., & Greenberg, J. M. (2016). Estimating community-level costs of preterm birth. Public Health, 141, 222–228

- Lakshmanan et al. (2022). Financial burden experienced by families of preterm infants post-NICU discharge. J Perinatol, 42, 223–230

- O’Neil et al. (2022). Societal cost of maternal morbidities in the U.S. PLoS One, 17(10), e0275656