Low-Wage Workers in High Demand: Seeking a Way Forward in Home Health Care

Posted in Blog

HCFI Research Brief by Carol B. Davis, Teneil Brown, Vidhur Krishna, and Thomas DeLeire

November 2021

In 2021, our HCFI team has been combing through the research and reporting on post-acute healthcare delivery and financing during the pandemic, to distill longer term public policy implications and lessons. An important topic caught our interest at the intersection of several policy debates: proposals for a $15 federal minimum hourly wage, the recognition of essential workers, and the rising demand for home health care.

These three issues converge in the case of home health aides, the people who provide direct hands-on support to patients with daily tasks and basic care, and who comprise the majority of direct care personnel in home health agencies. In a series of installments on our HCFI blog page, we will explore various aspects this issue. In this initial post, we describe the current home care aide workforce, including their characteristics, wages, and incomes, and the trends converging to elevate this often overlooked occupation to a pivotal position in the transformation of home care delivery for America’s elderly and disabled.

What’s causing a shortage in home care staffing?

Among the seismic movements in healthcare during the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (PHE) is a shift towards home health care. Fear of COVID exposure in institutional settings may have accelerated trends spurred by demographics, cultural shifts towards aging in place, and financially-motivated experiments with hospital-at-home. In addition to often being less expensive, and more convenient, home health has offered an option for patients rendered homebound by fear of COVID-19 exposure in institutional, or even outpatient care settings.

The Home Care Association of America estimates that 40% of seniors require assistance with daily tasks, and that 70% Americans over the age of 65 will need assistance at some point. AARP reports that one in five seniors will require home care or home health support for more than 5 years. National Center for Health Statistics estimated 4.5 million users of home health agencies in 2016.

In many areas, there were already high job vacancies and long waits for service in home care prior to the upheaval of the pandemic. After an initial drop in service volume at the beginning of the pandemic, home health volumes rebounded by late 2020. As the capacity to serve home care patients is a direct function of the available home care personnel, it is necessary to increase the number of people willing to work in this essential occupation if providers are to meet the growing demand. The combination of these factors has home health agencies struggling to maintain adequate staff.

How many people work as Home Health Aides?

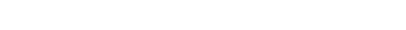

Home Health Aide (HHAide) is one of the largest of the essential, frontline occupations1, and they are the mainstay of the home care labor pool. The BLS reports 3.2 million people were employed as HHAides or Personal Care Aides in 2020, serving elderly or disabled residents, either in care facilities or at home. The 863,850 HHAides are the majority of the patient-facing staff in home health care services. HHAides and other support workers were 62% of the workforce in home health agencies in 2020, compared to registered nurses who comprise 12% of Home Care Agency personnel. (Figure 1). The BLS projects rapid growth in the demand for home health aides, at 33% or more than 1 million new positions over the next 10 years.

Source: National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment Estimates for NAICS: 621600 Home Health Care

Services, May 2020 and 2019, Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor.

Figure 1: Home Health Services Employment by Occupation, 2020

What do Home Health Aides do?

HHAides assist people who have disabilities or chronic illness with daily activities, or support their recuperation at home in order to postpone the need for admission to hospital or a residential care facility. HHAides generally provide non-medical services, but under the supervision of a nurse or physician, they may assist with administering medication or performing basic exercises or ambulation.

Who is the “typical” home health aide?

Data from the American Community Survey (ACS) helps us better understand the home health aide workforce and provides context to proposals to increase the size and stability of home care personnel needed for the expected increase in demand.

Source: HCFI Analysis of data from the 2019 American Community Survey from IPUMS

Figure 2: Demographic Characteristics of Home Health Aides, 2019

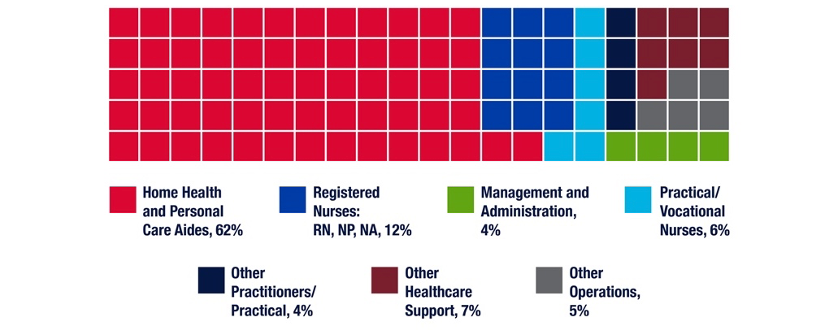

The vast majority of HHAides are women (90% in 2020), 47% are non-white. 66% of HHAides have a high school diploma or less formal education. Immigration appears to be an important source of home health care aides, with over 30% of HHAides who responded to the ACS reporting that they were either naturalized citizens or non-citizens. Nearly half (49%) are heads of households, and 44% of HHAs were in a household with children. (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Family Composition of Home Health Aides, 2020

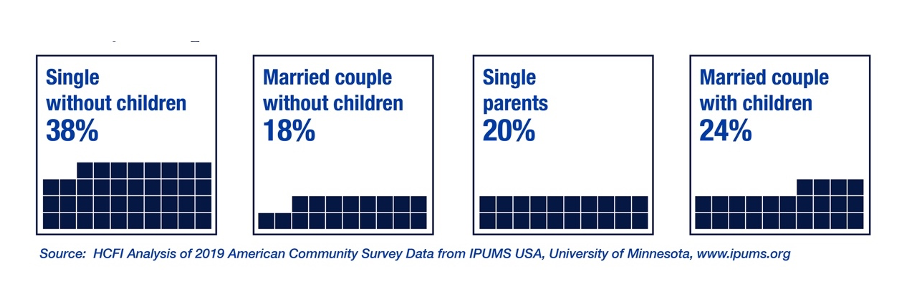

On average, family income for home health aides is below national averages. Forty percent are poor or near-poor ( defined here as having 2020 household income at or below 200% of the Federal Poverty Line) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Home Health Aide Family Income, 2020

How much do Home Health Aides earn?

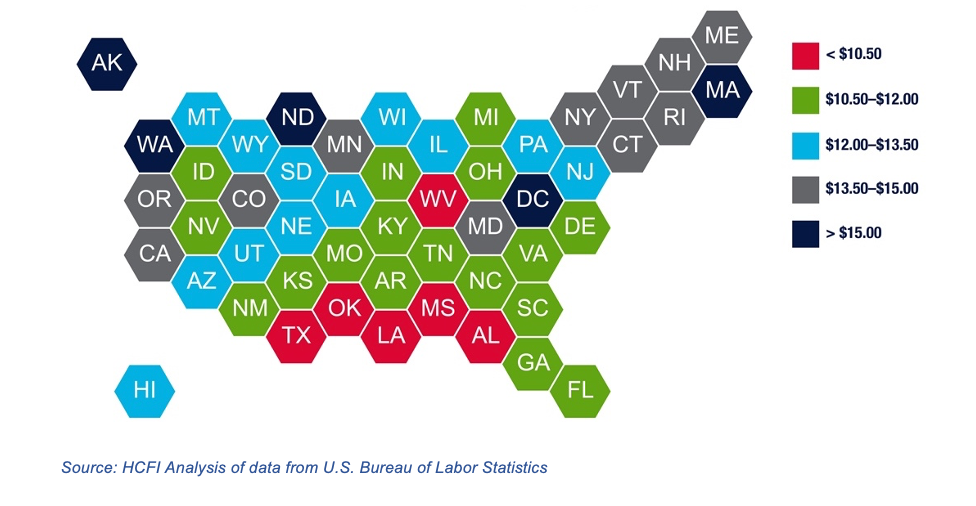

The median wage for home health aides was $13.02 in 2020. Our analysis of data from the BLS found that ~75% were below $15. Low median wages for HHAides is concentrated in the southern states, and the concentration of relatively higher median wages for HHAides is in the northeast and on the west coast. Massachusetts and Louisiana represent the highest and lowest median wages, at $16.66 and $9.04 respectively. (Figure 5)

#HHA2020MedHex

Figure 5: Median Hourly Wage of Home Health Aides, 2020

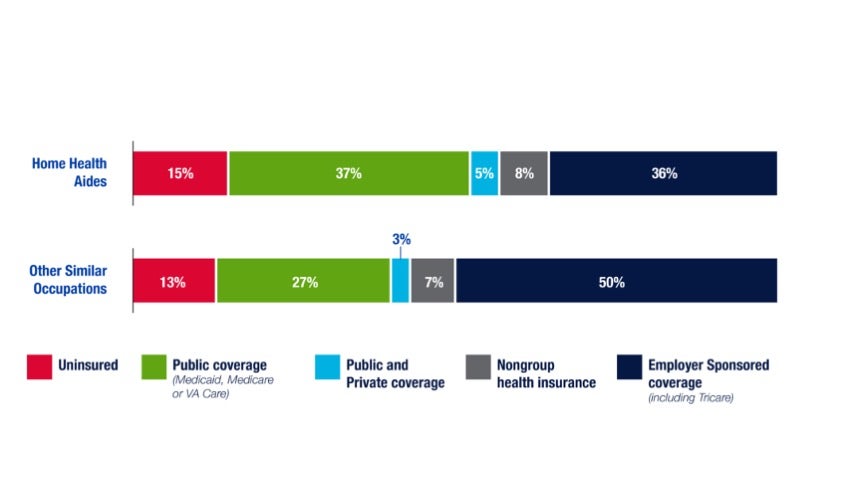

Eighty-five percent of HHAides responding to the ACS were in families with health insurance. Nearly equal numbers of respondents reported having exclusively public coverage (Medicaid, Medicare or Veterans’ Affairs) as reported having insurance provided by their or a family-member’s employer. Compared to other similar occupations (orderlies, psychiatric aides, nursing aides), home health aides appear to be more dependent on public coverage for health insurance. HHAides were slightly more likely to be uninsured than people in other similar occupations. (Figure 6)

Source: HCFI Analysis of 2019 American Community Survey Data from IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipumsorg

Figure 6: Health Insurance Coverage of Home Health Aides, 2019

Would Legislative Proposals Boost the Home Health Aide Labor Pool and their Wages?

What will it take to grow the number of HHAides and stabilize the workforce to meet the rising demand? How will public policy and labor policy demonstrate the newly recognized value of home health workers? For one thing, they’ll probably need higher pay.

In 2021, there have been several bills or policy proposals that could directly or indirectly result in increased wages for home health aides and similar occupations. The Raise the Wage Act, introduced in January 2021 proposed increasing the Federal minimum hourly wage from $7.25 in 2021 to $15 by 2025. The Choose Home Care Act of 2021 would expand Medicare recipients’ coverage for home health as an alternative to facility-based skilled nursing care. Neither of these proposals at the federal level have garnered the momentum and broad bi-partisan support that would suggest enactment is imminent. The Build Back Better Act, a package of social investments which recently passed in the House of Representatives includes a provision to increase Medicaid funding for home health care services. The proposal’s fate in the Senate is still uncertain. Nonetheless, the recurrent theme of more resources for and more access to home care is a distinct pattern in the policy issues prominent this year.

In actuality, patchwork of federal, state, and local minimum wage laws governs the hourly wage floor, terms for how the wage should increase over time, and the scope of the labor market or which employers are subject to the laws. As of September 2021, thirty states have minimum wages that already exceed the current federal minimum of $7.25. It remains to be seen whether legislation or market forces will prevail in increasing the wages of home health aides.

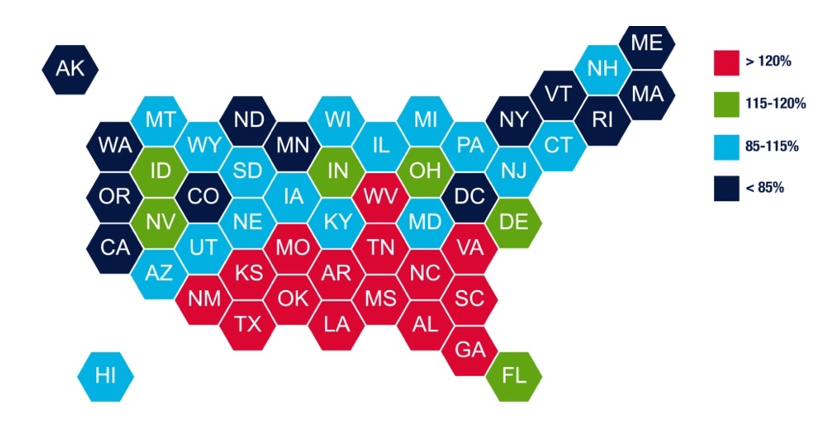

Source: HCFI Analysis of data from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Minimum Inflation Projection from US. Dept of Commerce and a variety of sources

Figure 7: Ratio of Proposed $15 Minimum to Projected Median Wage, 2025

We projected the current median HHA hourly wage at a modest growth rate of 2% annually and compared that to the $15 proposal in 2025 (Figure X). The effect on HHA wages could be very limited in over half the states on track to have minimum close to or exceeding $15/hour (shown in shades of blue in Figure x). For 15 states in the south and south east, the $15 minimum would be a boon to HHAs (shown in red in Figure X). However, the boost in wages would also represent a material increase in labor costs that would require additional management or policy decisions to ensure the burden lands fairly between home health agencies, patients, and taxpayers.

It may also be the case that wage increases are a necessary, yet insufficient remedy to the shortage of home health care workers. (Read: emphasis on both necessary and insufficient). Recent reports from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) describe record level of employees leaving their jobs in 2021. The data is reported at the industry level, so the specific impact within the specific occupation of home care aide cannot be inferred, but other industry watchers2 include health care workers among the sectors experiencing remarkable levels of vacancies, with workers reporting burnout and dissatisfaction made worse by the pandemic as reasons for leaving or seriously considering doing so.

In September, HCFI featured an interesting article by Dr. Stephen Landers of the Visiting Nurse Association offering creative innovations to elevate and grow the professional nursing staff in home health. We expect that equal creativity and resources will be required to grow the entire Home Health Agency patient care roster, including the home health aides.

Our team at HCFI is working to understand how various policy proposals and market trends will impact home health in the years ahead.

Lead author Carol Davis is an assistant research professor at McCourt School of Public Policy, Georgetown University; Teneil Brown is a programmer/analyst at McCourt and analyzed the CPS and ACS for this brief; research assistant and McCourt School MPP candidate, Vidhur Krishna analyzed the BLS data for this brief. This work was conducted with the overall supervision and review of HCFI Director, Thomas DeLeire, professor at the McCourt School.

Follow our work on Twitter: @GUHealthFinance or on the web: http://hcfi.georgetown.edu

For more insights on the dynamics of Home Health that emerged during the pandemic, see publications from our contributors…

The Looming Reorganization of Skilled Nursing and Home Health Services, by John McHugh PhD, MBA; Dori Cross PhD; and Bradley Flansbaum, DO

Home Health Growth Requires Innovation in Nursing Education, by Dr. Steven Landers

Notes/References

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook, Home Health and Personal Care Aides

- As reported in a variety of publications, including Harvard Business Review, Money Magazine